The sinking of the Friedrich Albert and the remarkable medical skill of an Icelandic country doctor

Being on board a ship that runs around and having to fight for one´s life in the freezing cold waters and winter darkness off Iceland´s coast must be a harrowing experience. However, one ship wreck judged to have been more terrible than all the rest was the sinking of the German trawler, the Friedrich Albert, in 1903. No one knew of the stricken vessel’s plight and the survivors only made it to safety after days of suffering in frightful weather conditions. Here is an incredible story of human endurance of heroic proportions and the remarkable medical skill of a local country doctor.

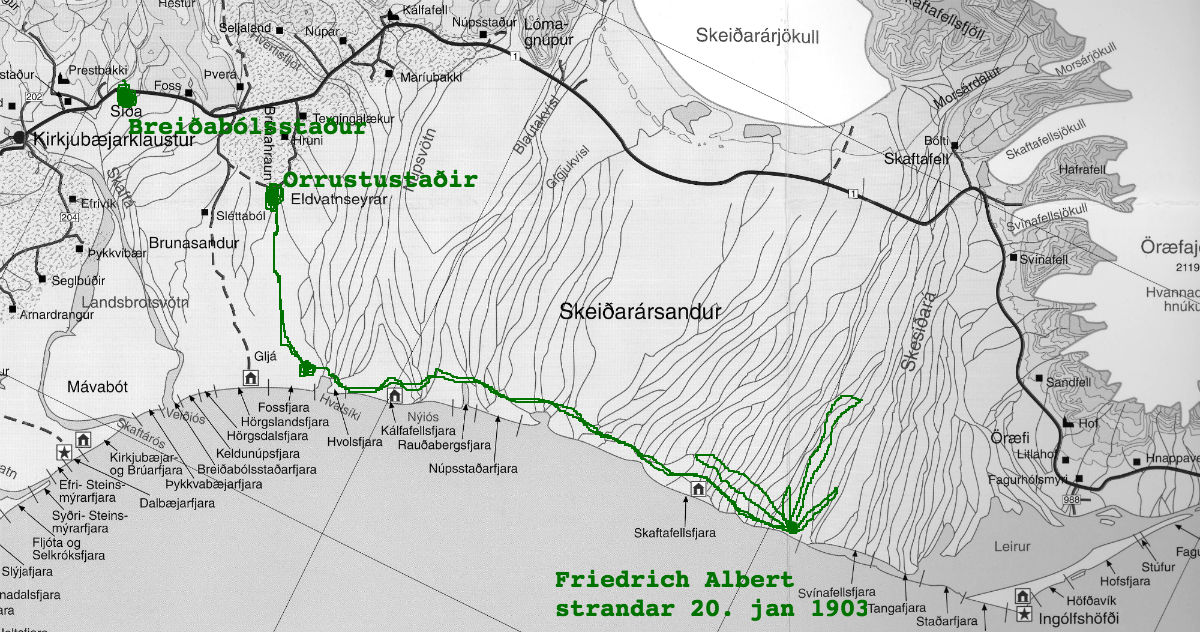

A German trawler runs aground on the Skeiðará river sands

In early January 1903 the German trawler Friedrich Albert from Bremerhaven ran aground on the Skeiðará river sands on Iceland´s south coast. The crew bound themselves to the mast with a rope as the huge waves crashed over the stricken vessel. With great difficulty they managed to make it ashore once the storm had abated.

On the morning of 20 January, the crew of 12 stood wet and without provisions on the desolate sands miles from the nearest farms. Weather conditions were dire; it was freezing cold, snowing and a strong wind was blowing. The men tried to salvage some food from the wreck and succeeded after two days. They then proceeded to erect a makeshift shelter using the ship´s sail and lifeboat and various other salvaged items.

Taking on the powerful glacial river estuary

The burning question was how to get to the nearest farm and safety. The crew set off westwards in the direction of Lómagnúpur Mountain. At one point along the way they sank deep into the treacherous wet sands and only saved themselves by desperately dragging each other out. Exhausted, they decided to return to the ship and take shelter. The following day they again tried to find an escape route, but the expansive glacial river estuary with its many channels always blocked their path. There was nothing for it but to head back to their makeshift shelter.

Another day they attempted to wade across Hvalsýki, but it became so deep that they dared not continue. By now it was dark and there was nothing for it but to spend the night out on the exposed sand bank. Four men decided to return to the stranded ship; two would give up and return to the sand bank while the other two continued on towards the ship. Throughout the night the captain woke his crew every half hour and had them move about so as avoid freezing to death. When dawn broke it was discovered that one crew member had died from exposure. Taking advantage of the daylight they retraced their steps back to the stranded vessel. On the way they found one of the two crew members who had headed back the night before barely alive. They franctically tried to revive him but without success. When they reached the ship there was no trace of the second crew member and his fate would never be known.

A man far in the distance – hope, despair, freezing cold and frostbite

By now the crew members were utterly exhausted and had abandoned any hope of surviving. Nine were alive. Two were dead and one was missing. They were convinced the situation was hopeless and that there was no way of fording the icy rivers flowing across the sandy wasteland. But the captain doggedly refused to give up and suggested building a raft that might get them across the glacial flood waters. Only one crew member had the necessary strength to build the raft, the others were far too weak. They were cold, wet and without food, and some were now suffering from frostbite.

Taking the raft they set off for one last desperate attempt. Nearing the river they spotted far in the distance on the opposite bank what appeared to be a man or men on horseback. Desperately, they tried to attract their attention, but in vain. As the rider disppeared from view they took some small comfort from the fact that there was a glimmer of hope of finding help. They launched the raft and sailed it across the deepest parts, as well as wading where the river was shallow enough. It was now ten days since the stranding and the bitter weather had been relentless. That night there was a severe frost. They found some debris from the ship that provided some shelter from the wind, but the intense frost cut to the bone and they had no way of warming themselves or drying their sodden clothes.

Ten days after the shipwreck they reach a farm

The following day they travelled in the direction of where they had seen the man on horseback and eventually reached the farm Orrustustaðir. The locals immediately offered assistance. The district sheriff in the village of Kirkjubæjarklaustur was sent for, as well as the doctor at Breiðabólsstaðir. When the doctor arrived the frostbitten feet of the crew had almost thawed and he could evaluate just how serious their condition was.

Five serious cases of frostbite

The doctor´s examination revealed that five of the survivors were suffering from severe frostbite, two in particular. The next day four of the crew went on horseback to Kirkjubæjarklaustur and three were moved to the medical station at Breiðabólsstaður. Two of the crew stayed longer at Orrustustaðir before being moved to the medical station.

On horseback to Reykjavik on 5 February

The four men whose condition was not serious rode to Reykjavik on 5 February, accompanied by three local men, Lárus Helgason, Sigurður Pétursson and Eiríkur Steingrímsson. It seems unbelievable that the four were well enough to travel despite having endured 11 days in severe winter conditions, wet and without food and shelter. Among the four was the ship´s captain who played a central role in the men´s survival by constantly keeping their spirits up and building the raft that would save their lives. In Reykjavik the plan was to get the needed bandages and medicine for the five injured crewmen.

Two buried at Prestbakki cemetery, one missing

The district sheriff sent men familiar with the sands to the location where the ship was stranded in the hope of finding the bodies of the two dead crewmen and to see if there was any sign of the one still missing. At this point the ship had sunk deep into the sand, which made it impossible to salvage anything. What debris did drift ashore was of little or no value. This was in accordance with the opinion of the captain who felt there was no hope of saving the ship or anything on board. The bodies of the two who died were recovered in March and their remains buried in the graveyard at Prestsbakki. No trace was ever found of the missing crew member.

Guðlaugur was the sheriff at Kirkjubæjarklaustur, he is pouring coffee in the middle. Up in the left corner is Rev. Sveinn Eiríksson standing. (Photo EG)

The operating room would be the parlour at Breiðabólsstaður, the surgery being performed on the parlour table two weeks after the men had been rescued. This house was not there 1903 but part of it is the old house where the surgery was made. (Owner GR)

An amazing feat of medical skill

Bjarni Jensson was the resident doctor at Breiðabólstaður. He quickly realized that the men´s lives could only be saved by amputating the frostbitten limbs. He requested that Dr. Þorgrímur Þórðarson, who lived on the farm Borgir in the east, should immediately be called upon. The latter´s skill in amputation was well known. It took Þórðarson six days to traverse the difficult terrain and rivers and reach Breiðabólsstaður. On his arrival he quickly took control of matters. He wrote a letter to the sheriff at Kirkjubæjarklaustur requesting that Rev. Sveinn Eiríksson come and assist him. Another minister, Rev. Magnús Bjarnarson at Prestbakki, also came to help. The doctor further requested that the sheriff himself come and assist so that the operations could proceed. The patients were terrified. They demanded that the sheriff confirm that it was safe to trust the doctor for the amputations. This placed the sheriff in a difficult situation. The procedure would be both life-threatening and costly, but it was even more dangerous to risk moving the men. The sheriff agreed to all the doctor´s demands and convinced the men that the doctor was fully capable of carrying out the difficult procedure.

Limbs amputated and the wounds fully heal within two weeks

The operating room would be the parlour at Breiðabólsstaður; the surgery being performed on the parlour table two weeks after the men had been rescued. The housewife, Sigríður Jónsdóttir, saw to boiling the water and sterilizing the surgical instruments. Five patients needed to be operated on. In all eight feet were amputated, two below the knee and six at the ankle. First just the toes of some were amputated, but this proved not to be enough and so the entire foot as far as the ankle was removed. When it was necessary to amputate both feet of the same patient, a lapse of one week was allowed between operations. After surgery the wounds had to be cleaned and dressed for several weeks. What is remarkable is that the records show that all wounds had healed within two weeks. It was a major undertaking to treat the men before and after the operation. The midwife, Guðríður Jónsdóttir, was the nurse who cared for the men the entire time. Receipts show that she was paid for 85 days´ work and that she had changed the dressings on the wounds of the five men 20 times.

The midwife, Guðríður Jónsdóttir, was the nurse who cared for the men the entire time. (Owner SSk)

Bjarni Jensson, the doctor on Breiðabólsstaður, and his wife Sigríður Jónsdóttir. The surgery were made in their house and the patients stayed there for months untill the wounds were healed. (Owner Skógar Museum)

No infection of wounds and the making of special stirrups

The doctor and his wife at Breiðabólsstaður did all in their power to save the seamen´s lives and make them as comfortable as possible the four months they were recuperating in their home. It was the responsibility of the sisters Sigríður and Guðríður to ensure the wounds did not become infected. They saw to any steralization and were careful to maintain a high standard of hygiene in the home to prevent the wounds becoming infected and gangerine setting in.

The German seamen remained until the beginning of May, even though their wounds had healed, because it still was not possible to traverse the sands. Four could travel to Vík and take a boat from there to Reykjavik. A local farmer had made crutches and special stirrups lined with skin and wool. The last of the five needed more time to recover and left for Reykjavik in mid May.

Icelanders awarded the Prussian Silver Cross and a decorative brooch

Initially the crewmen had little confidence in the two Icelandic doctors. However, after the operation their attitude completely changed when they saw how quickly their wounds had healed. At that time there is no mention as to the mental state of the survivors, no doubt their terrible experience must have had a deep emotional impact. Nevertheless, they survived this terrible ordeal and it is a miracle that they did.

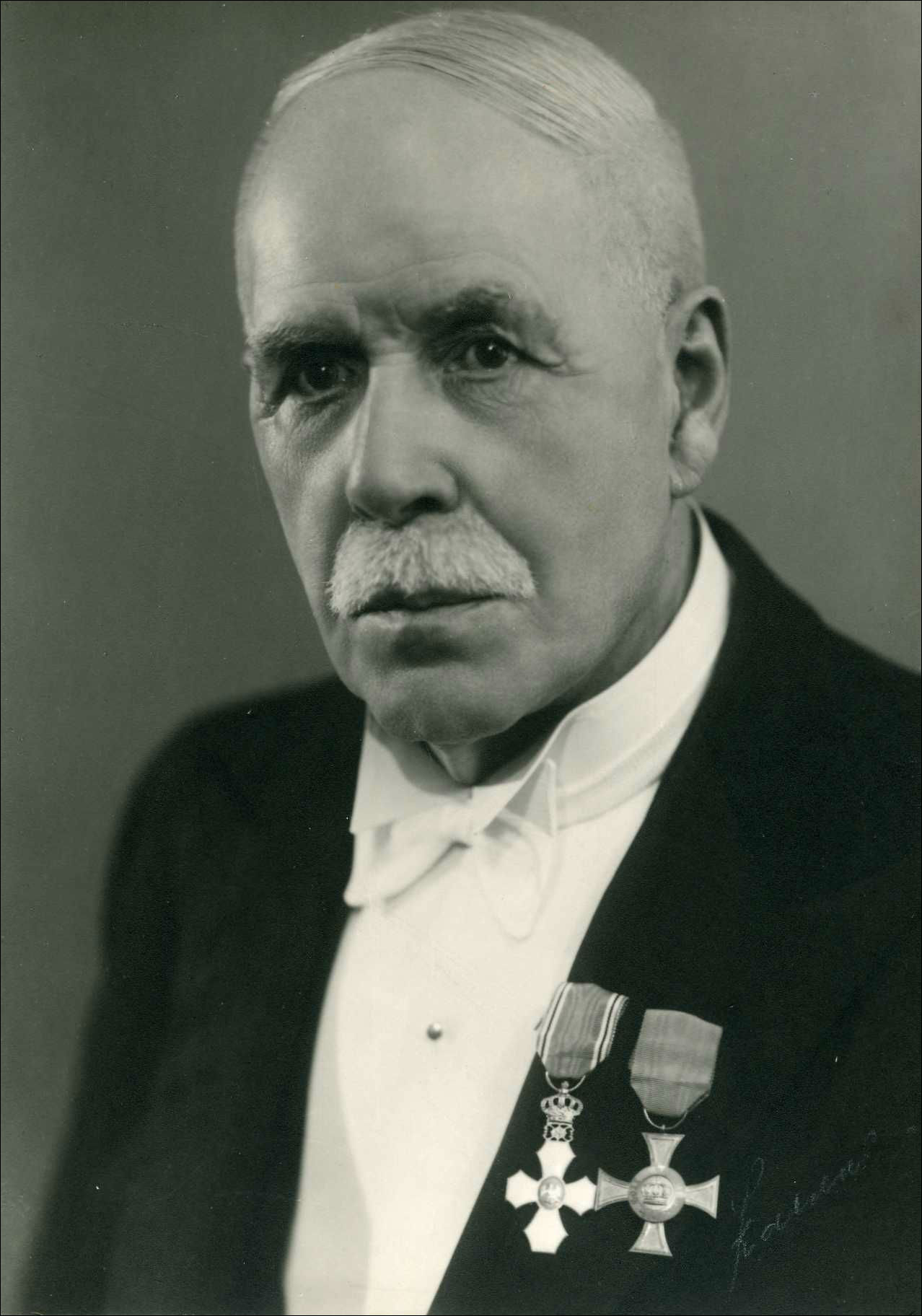

How the crewmen of the Friedrich Albert successfully endured terrible physical hardships and the outstanding medical skill of the Icelandic doctors treating them is a remarkable story. In recognition of the care provided, the German government awarded both Icelandic doctors the Prussian Order of the Eagle and the midwife Guðríður Jónsdóttir a brooch. The brooch was crown-shaped and very beautiful. However, many found it strange that Sigríður Jónsdóttir did not receive any formal recognition. Both clergymen received the silver cross. All would agree that the actions of these good folk were more than deserving of the awards conferred.

The minister, Rev. Magnús Bjarnarson at Prestsbakki, also came to help. Here you can see the silver cross (to the right). Both the clergyman received the silver cross from the German government. (Owner IH)

[1] Kristinn Helgason. 2001. Dynskógum 8. Útg. Vestur-Skaftafellssýsla, Vík. Bls. 19-41.

[2] Þórarinn Helgason. 1957. Lárus á Klaustri. Bókaútgáfa Guðjóns Ó Guðjónssonar. Rv. s. 330

[3] Bjarni Jensson og Sigríður Jónsdóttir, læknishjón á Breiðabólsstað á Síður og í Reykjavík. 150 ára minning. Bjarni Bragi Jónsson skráði og gaf út 2007.

[4] Steinar J. Lúðvíksson. 1980. Þrautgóðir á raunastund. XII. bindi. Bókaútgáfan Hraundrangi – Örn og Örlygur hf.