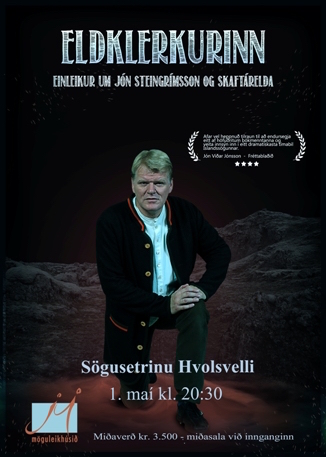

Just who was Rev. Jón Steingrímsson and where did he come from? This charismatic clergyman would record the history of Iceland´s most devastating volcanic eruption and with his powerful sermon stem the flow of the encroaching lava that threatened to destroy his church in the village of Kirkjubæjarklaustur.

A short film, Eldmessa, has been made of the Laki eruption and the famous “fire sermon” preached by Jón. The film can be viewed online for a small fee or for free in the Information Center Skaftárstofa in Kirkjubæjarklaustur

Model of the Old Church in Kirkjuklaustur is in the Minningarkapella Jón Steingrímsson.

A northerner forced to move south due to scandal

Jón Steingímsson was born and raised in Skagafjörður in the north of Iceland in 1728. He lost his father at a young age, but through the intersession of good folk he was admitted to the school at Hólar bishopric. Upon completing his studies he was appointed deacon at Reynistaður church. After the pastor´s death, Jón began a relationship with his widow, Þórunn Hannesdóttir Scheving (1718-1784). Rumour had it that the pastor had died under suspicious circumstances and some even suggested that Jón had a hand in it. The case would go to court and Jón was judged to be totally innocent of the serious charge levelled against him. Soon afterwards Jón would father a child with Þórunn, Sigríður by name. But this was before the couple were officially married in 1753 and the resulting scandal meant Jón could not be ordained.

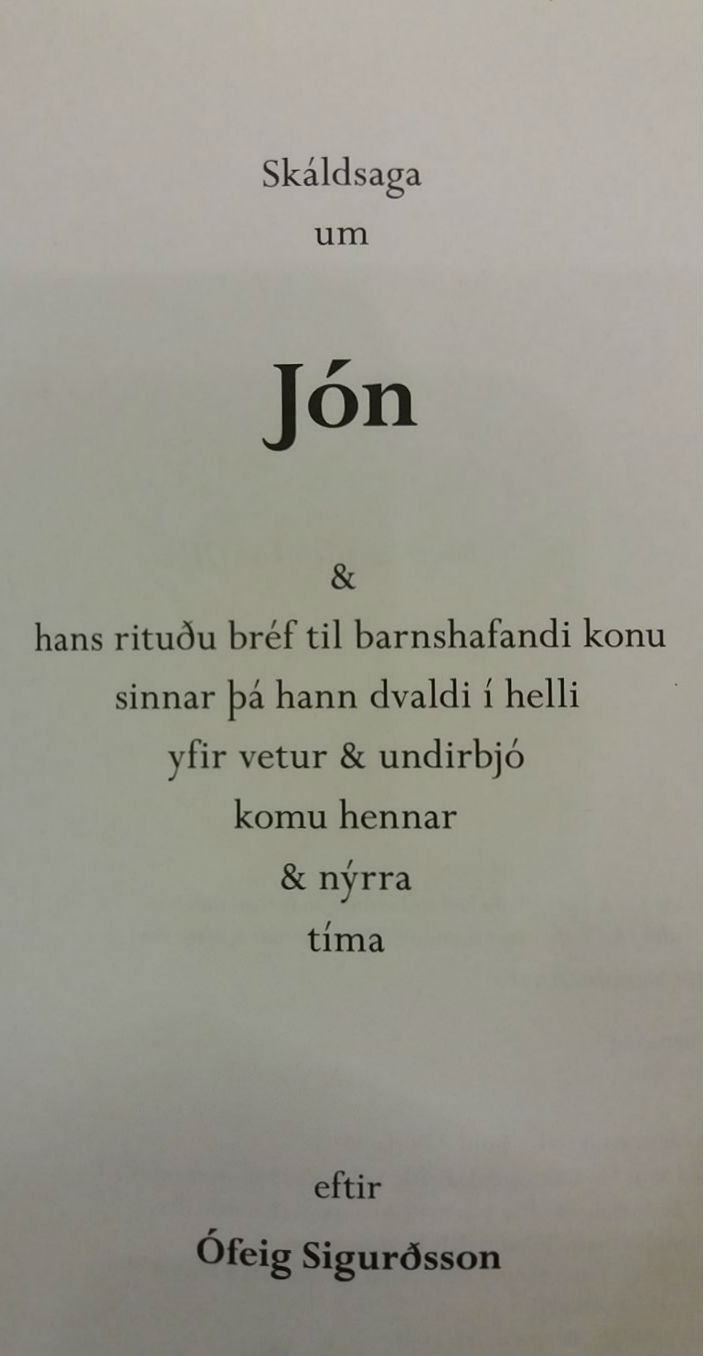

No doubt this awkward situation and the associated gossip would have been one of the main reasons why Jón and his wife considered moving away. Þórunn was wealthy and she or her children had inherited the farm Reynir in Mýrdal on the south coast. The decision to move south was finally taken after Jón failed to find a suitable place to live in the north. Jón first went south with his brother and for a time lived in a cave in Mýrdal while a house was being made ready. In the same winter of 1755, the subglacial volcano Katla violently erupted. Jón followed the eruption with keen interest and made notes. Later, Þórunn would travel south with the three children from her previous marriage and the daughter Sigríður that she had with Jón. Þórunn was also now pregnant with Jón´s second child. Eventually, in 1761 Jón would be ordained at Skálholt cathedral. Seemingly enough time had elapsed for his earlier sexual impropriety to be forgiven.

His relationship with the locals in Mýrdal was at times strained

Jón would become the pastor at Felli in Mýrdal and would serve there for 17 years. In 1774 he was appointed provost for the district of west Skaftafell and later for both east and west districts.

Jón farmed all the years that he was a clergyman. He was a man of foresight and action and made many improvements to the farm at Felli. In this matter, he was quite unselfish in that the farm was not his but the property of the Danish crown. Jón also studied medicine, gleaning information from books and learning from his friend and state physician, Bjarni Pálsson. Jón would often have people stay at his home in order to treat them or travel to people´s homes if necessary. He seemed to have a natural talent and knew the medicinal value of plants. His friend Bjarni also provided him with medical instruments.

So renowned was Jón for his medical skill that he was much in demand throughout the entire south. For his humanitarian endeavours and the improvements at Felli Jón was awarded a medal from the Danish monarch, King Christian VII. Jón was also granted Danish citizenship and the right to hold public office in Denmark. This would have given Jón the opportunity to flee Iceland had he so wished when calamity struck with the terrible Laki eruption in 1783. Instead, he chose to stay with his flock and care for them in their hour of greatest need.

Despite things going well for the family at Felli, Jón decided to move to the parish of Kirkjubæjarklaustur when the position of pastor became vacant in 1778. “After much deliberation and prayer, I took the decision to apply.” He had already had a series of disagreements with some of the locals, something he touches on in his autobiography. “Before receiving royal recognition I suffered much at the hands of bad and envious men. The more that God blessed me with good fortune the more they tried to blacken my reputation and injure me. One could say that in Mýrdal I had to endure the worst and most brutal individuals of the day. Jón goes on to describe in detail the disputes and is scathing in his criticism.

Happy times at Prestsbakki for Jón and his wife

The move to Prestsbakki proved to be a fortuitous one both for Jón and his new congregation. He describes the people as follows: “Here people were far more honourable and law abiding than those in Mýrdal; they are cordial towards their pastor and observant in their duties, with one exception.”

While many things can be said about the Reverend Jón Steingrímsson, he would prove himself to be a pillar of strength to his flock when the Laki eruption occurred in 1783. He never abandoned his community, something other ministers quickly did when disaster struck. What he is most famous for is the impassioned sermon he preached in the church at Kirkjubæjarklaustur – a sermon many believe caused the lava flow to miraculously stop and the church to be saved. As a result, Jón would be given the name the “fire pastor” and his “fire sermon” would write itself into the Icelandic history books. The sermon, Eldmessa, Fire Mass, was given on 20 July and ever since this remarkable event is celebrated by serving ministers at Klaustur.

Þórunn and her daughters

Þórunn Hannesdóttir Scheving stood firmly by her husband through thick and thin and Jón was always unsparing in his praise of her. When she was a teenager her stepfather was so amazed by her intelligence and her sharp perception that he passed the following remark: “Oh, what was the Lord thinking of that you were not a boy. You know everything and remember everything.” Þórunn was 60 years of age when they moved to the parsonage at Prestbakki in the parish of Kirkjubæjarklaustur. Þórunn managed a large home and no doubt shouldered considerable responsibility both in and outside the home as Jón was often away for long periods either on pastoral work or tending the sick.

After the eruption, Jón would generously offer shelter at the parsonage to those who had lost their homes; a gesture that would have resulted in even more work for Þórunn. Jón speaks glowingly of his wife and to all accounts theirs was a happy marriage. Þórunn had three child from her previous marriage. Þórunn and Jón had five daughters: Their names were Sigríður (born 1753), Jórunn (born 1755), Guðný (born 1757), Katrín (born 1761) and Helga (born 1762). All of these women would go on to marry clergymen.

Þórunn and 75 others would die the same year

According to Jón, the darkest period of his entire existence was 1784, the year his wife passed away. The situation in the district was dire with deaths occurring daily. That year alone 76 of Jón´s parishioners died and there was only one horse to carry the remains to the cemetery. Jón took some solace from the fact that it was possible to provide coffins for all the dead, but he admitted that sometimes it was necessary to bury six, eight or even 10 corpses in the same grave. Remnants of these mass graves can still be seen in the southwest corner of the old cemetery in Klaustur. This is one of the few examples of mass graves to be found in Iceland. Some were buried in outlying cemeteries as there were insufficient people to help bring the dead to Klaustur for burial. Jón refuted rumours that some had been buried in unconsecrated ground. It must have required great strength of character to survive the catastrophic fallout of the Laki eruption. Despite the natural and human devastation, Jón never lost hope. He stayed firmly loyal to his parishioners and did everything in his power to alleviate their suffering. And God was “merciful” to his people, for a ship would run aground and it was possible to salvage flour, hemp, iron and other items.

Re. Jón Steingrímsson´s autobiography – a milestone in Icelandic literature

The story of Rev. Jón´s impassioned “fire sermon”, delivered in the little church in the village of Kirkjubæjarklaustur and how the advancing lava flow suddenly stopped, is one of the most dramatic stories in Icelandic history. Jón was a deeply complex person living at a time of change and from his autobiography, one can learn much as to that age in Iceland’s history.

The manuscript was to be destroyed

That Jón came to write his autobiography and that it was not destroyed is nothing less than a miracle. The autobiography was kept by his daughters after his death. One of them agreed to lend the manuscript to Jón´s nephew in Reykjavik, Bishop Steingrímur Jónsson, on the condition that he would destroy it after reading it. The manuscript was deemed to contain various matters of a very personal nature that his daughters felt should not be made public. However, the bishop did not do as requested. Instead, he kept the manuscript and just over a century later, in the years 1912-1916, it would be published in its entirety.

[1] Ófeigur Sigurðsson. 2010. Skáldsaga um Jón & hans rituðu bréf til barnshafandi konu sinnar þá hann dvaldi í helli yfir vetur & undirbjó komu hennar & nýrra tíma. Mál og menning, Rv. Í þessari bók segir frá dvöl Jóns og bróður hans í hellinum.

[2] Einar Laxness. 1985. “Á 200 ára afmæli Skaftárelda.” Dynskógar 3. Vestur-Skaftafellssýsla, Vík. s. 101 Þetta er líka í grein í Læknablaðinu og þar er bein tilvitnun í greinargerðina sem fylgdi verðlaununum. Örn Bjarnason. 2006. “Síra Jón Steingrímsson – líf hans og lækningar.” Læknablaðið 12. tbl. 92. árg. Desember 2006 s. 891

[3] Jón Steingrímsson. 1973. Æfisagan og önnur rit. Helgafell, Rv. s. 189

[4] Jón Steingrímsson. 1973. Æfisagan og önnur rit. Helgafell, Rv. s. 189

[5] Jón Steingrímsson. 1973. Æfisagan og önnur rit. Helgafell, Rv. s. 249

[6] Jón Steingrímsson. 1973. Æfisagan og önnur rit. Helgafell, Rv. s. 381

[7] Gísli Gunnarsson. 2002. „Börn síns tíma.“ Skírnir 176. haust s. 308

[8] Matthías Viðar Sæmundsson. 1996. „Sjálfsævisaga klerksins.“ Íslensk bókmenntasaga III. bindi. Mál og menning, Rv. s. 132

[9] Einar Laxness. 1985. „ Á 200 ára afmæli Skaftárelda.“ Dynskógar 3. Vestur-Skaftafellssýsla, Vík s. 97

[10] Jón Steingrímsson. 1973. Æfisagan og önnur rit. Kristján Albertsson ritaði formála. Helgafell, Rv. s. 18-19 Báðar þessar ritgerðir er að finna í þessari útgáfu Æfisögunnar en Lækningar eftir stafrófinu er varðveitt á Þjóðdeild Landsbókasafns Íslands JS 647 4to.

[11] Skaftáreldar 1783-1784. 1984. Mál og menning, Rv. s. 272