Kjarval’s Birthplace

Jóhannes Sveinsson was born in 1885, on the farm Efri-Ey in Meðalland, the ninth of thirteen siblings. His artistic eye saw the first rays of the sun in Meðalland, where he played with his sisters and other children. His parents were Sveinn Ingimundarson and Karítas Þorsteinsdóttir, both born and raised in Meðalland. After having lived in Efri-Ey for 27 years, they moved to Suðurnes in 1899 and later they moved to Reykjavík. (Photo by Willems Van de Poll)

Kjarval’s Early Years

When he was just four years old, Jóhannes Sveinsson left Meðalland and went to live in Borgarfjörður in the Eastfjords, where he was fosterd by Jóhannes Jónsson and his wife, Guðbjörg Gissurardóttir. Jóhannes was Kjarval´s uncle on his mother´s side. In Borgarfjörður, Jóhannes reached adulthood by doing various traditional jobs and he also painted frantically in his leisure time. It was considered a point of his peculiarity that he was: „…always crafting and tinkering and painting“. Luckily, his cousins understood his talent, and when he was young they gave him dye used for wool to paint because, at that time, paper and drawing pencils were rare. But he managed to come by paper and pencils, and in time, his talent was recognized. People who were immigrating to America during those years asked him to paint their farms to have something precious to remember. Oftentimes, he would lie by the cabbage fence and paint the splendid sailboats entering the fjord.

Jóhannes took care of his cousins in their old age; they influenced him in his early life as an artist. They encouraged his desire for art and infused him with determination to continue his work

In 1901, when John was 16, he boarded the passenger ship Hólar on its way to Reykjavík. His parents boarded the ship in Keflavík, as they were moving to Reykjavik. They had not seen Jóhannes since he left Meðalland, 12 years ago.

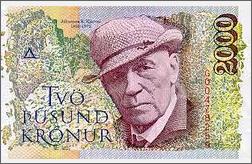

In the years to come, Jóhannes worked a variety of jobs, but when he was around 20 years old, he spent two winters at Flensborg School in Hafnarfjörður, where he showed excellence in drawing and his way to become an artist was paved. He earned a degree at the Royal Academy of Arts in Copenhagen in 1918. Before he left home, he took up the name “Kjarval”, which is an Irish Royal name. Kjarval stayed in Rome and later in Paris, and devoted himself fully to his art.

Kjarval’s Unique Depiction of Nature

Kjarval saw various images in cliffs and rocks that no ordinary eye could see. In the mountains and canyons he saw a face, sometimes even the faces of nearby farmers, and they can be recognized in some of his paintings. Kjarval was also fond of the legend of the “hidden people”. Nature was a sanctuary in his eyes. It has been said that Kjarval brought a new view of nature to Icelanders, and taught them to appreciate the beauty of the natural habitat. For instance, the rough lava was in the eyes of Icelanders nothing but the worst hindrance, but in Kjarval’s paintings, it appears to us in close-ups as a fascinating pattern of small-scale shapes and beautiful colors.

In the Artmuseum in Reykjavík you can find more about Kjarval and see his paintings

Kjarval the Pioneer

The importance of Kjarval in Icelandic Art History is indisputable, and Halldór Laxness, a 1955 Nobel Prize winner for Literature, who was 18 years younger than Kjarval, spoke unequivocally when he said:

“Kjarval’s work as a whole is all the more remarkable because, not only is he a great artist, but he is above all a pioneer and frontiersman. In a country where art expression was poor, until he reached his adulthood, the smallest gift from a man like him is a blessing”.

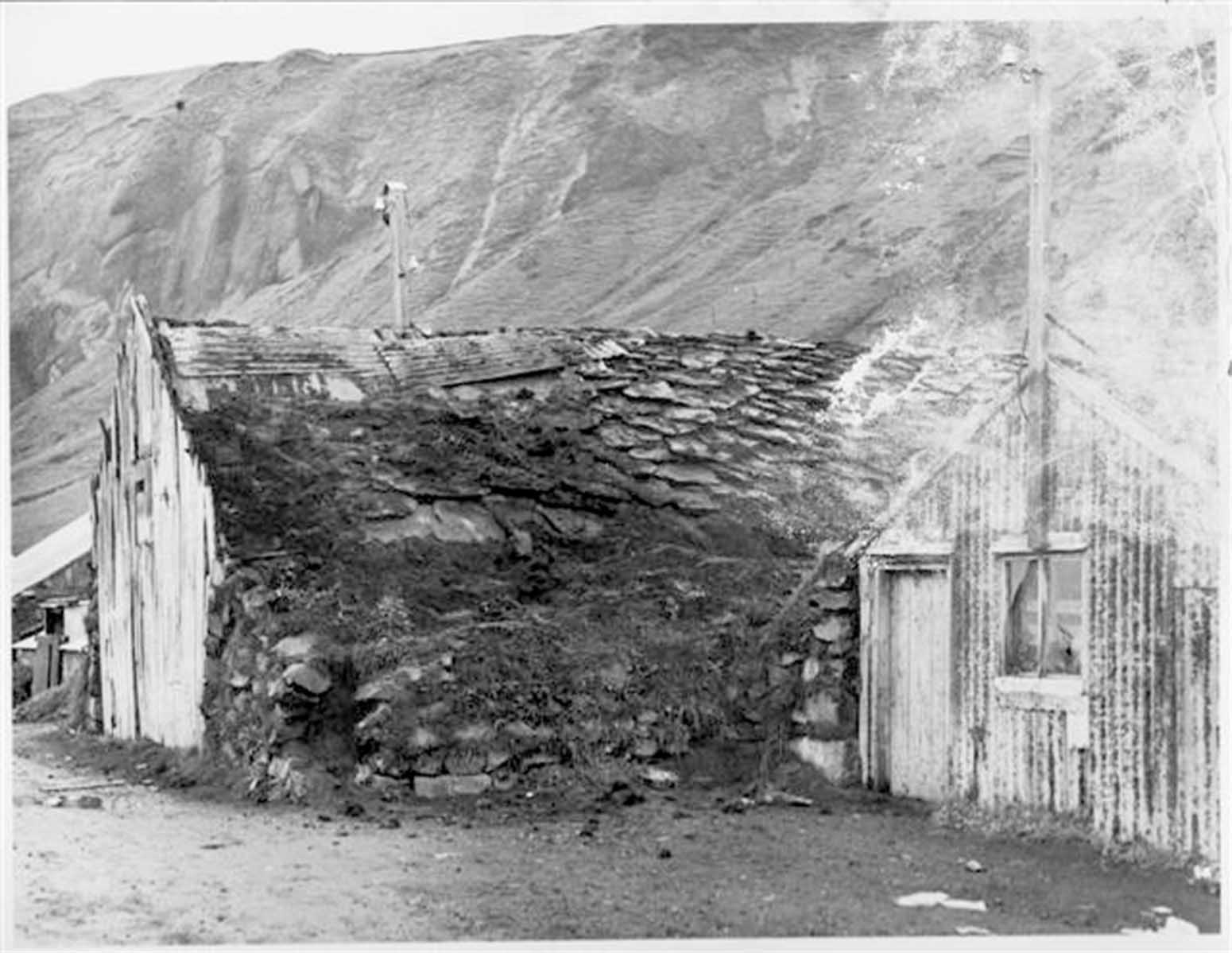

Kjarval wanted to preserve the old cowshed in Kirkjubæjarklaustur but got no counsil. It was torn down 1944. (Eig. EAV)

Kjarval painted the old cowshed so it would be preserved in any form.

Kjarval in Eldsveitir

Through his work, he turned a desolate landscape into an immortal piece of art. In the 1950s, he went to Klaustur in the summers to paint. He had a workshop in the old elementary school and he was well thought of and respected by the locals. He is known to have given away his paintings to people who were kind enough to offer him shelter, food, or drive him to remote areas where he could find inspiration to paint. Kjarval’s stay in Skaftárhreppur is memorable to everyone. He had a workshop in Kirkjubæjarklaustur. There the young boy Erró met him. 1974 marked the 1100 year anniversary of the first Nordic settlers in Iceland, and a lot of festivals were held to honor this event. One part of the celebration in Western Skaftafell County was a Kjarval exhibition at Kirkjubæjarskóli in Kirkjubæjarklaustur. The exhibition featured paintings by Kjarval owned by locals in Skaftárhreppur, 45 in total, many of which were given by Kjarval in the 1950s. The show was praised by many and they showed amazement for this art treasure that was hidden in such a small place.

There were many kids in Kirkjubæjarklaustur. Erró was the only one that was allowed to be in the old school when Kjarval was painting. (Eig. EAV)

The studio was in the old school on the right side of this photo. Erró grew up in the house next to the school. He got pencils and rest of the paint when Kjarval left in the Autumn. (Owner AL)

Kjarval the Reformist

Kjarval had an interest in the county’s welfare, and wanted to work on various reforms. For example, he designed a walkway over Skaftá, directly south of Kirkjubæjarskóli. He believed that the beauty of the Klaustur was best seen from south of the river. He often talked about the making of an airport to make flying to Klaustur possible, because traveling across the glacier waters was such a venture.

Giovanni of Efri-Ey

Kjarval called himself “fráfærulamb”, which is an Icelandic expression for the lambs which get separated from their mothers too soon. It is otherwise impossible to tell how he felt about being taken from his family and moved away at such a young age, but he obviously loved his birthplace, and the beauty of it. He even sometimes signed with the name Giovanni Efri-Ey.

Kjarval Paints

Kjarval painted a big picture

many felt it was a shame and a sin

that he should paint a moss and a rock.

They found the painting ugly.

Many years have passed since then

all began to think him bright.

No one complains the least bit anymore.

In the country side we look at a moss and a rock.

No one is heard to say: What a shame!

We say: Beautiful, like a Kjarval’s painting.

Þórarinn Eldjárn

Translated by Argyro Papagianni, The Poem was translated by María Sveinsdóttir

[1] Eyjólfur Eyjólfsson. 1985. „Hann málaði kögglana.“ Dynskógar 3. Vestur-Skaftafellssýslu, Vík. s.7 -9 (Þessi grein birtist í sýningarskrá á Kjarvalssýningu í Kirkjubæjraskóla árið 1974)

[2] Thor Vilhjálmsson. 1964. Kjarval. Helgafell, Rv. S. 20

[3] Thor Vilhjálmsson. 1964. Kjarval. Helgafell, Rv. S. 28

[4] Kristín G. Guðnadóttir, Gylfi Gíslason, Arthur C. Danto, Matthías Johannessen, Silja Aðalsteinsdóttir, Eiríkur Þorláksson. 2005. Kjarval. Nesútgáfan, Rv. s. 33-34

[5] Halldór Kiljan Laxness. 1950. Jóhannes Sveinsson Kjarval, inngangsorð eftir HKL. Helgafell, Rv. S. 26

[6] Sigurjón Einarsson. 1985. “Jóhannes S Kjarval í sveitunum milli sanda.” Dynskógar 3. Vestur-Skaftafellssýslu, Vík s. 15

[7] Sigurjón Einarsson. 1985. Jóhannes Sveinsson í sveitunum milli sanda. Dynskógar 3. Vestur-Skaftafellssýsla, Vík s. 19

[8] Björgvin Salómonsson. 1985. “Jóhannes S. Kjarval og Hallur L. Hallsson, heimildabrot um ævilanga vináttu.” Dynskógar 3, Vestur-Skaftafellssýsla. s. 58-60

[9] Sigurjón Einarsson. 1985. Jóhannes Sveinsson í sveitunum milli sanda. Dynskógar 3. Vestur-Skaftafellssýsla, Vík s. 33

Þórarinn Eldjárn. 2001. Grannmeti og átvextir. Vaka-Helgafell, Rv. S. 60