The supply ship Skaftfellingur operated for 21 years

Throughout the ages, the people of Skaftafells district had to undertake a long and difficult journey in order to purchase necessary provisions. The furthest they traveled was either westwards to the coastal town of Eyrarbakki or eastwards to Papós. In 1884 there were the beginnings of a store in the village of Vík. By 1900 locals were considering the possibility of having goods transported by boat to the Skaftá river estuary and by 1908 the estuary was officially designated a trading post.

Skaftfellingur now on exhibition in Vík

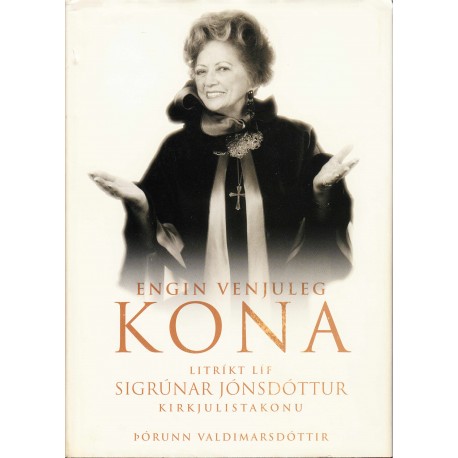

The vessel Skaftfellingur is now in a large hanger in Vík. A group of interested people have been working on setting up an exhibition telling the story of this remarkable vessel. The exhibition was formally opened on 4 June 2017. With the exhibition a chapter in the recent history of this region of the south coast will be preserved and told. The 18th of May 2018 was a celebration of the 100th anniversary of Skaftfellingur. Many people came to celebrate. The three sons of Sigrún Jónsdóttir and one daughter came and told the story about how their mother did manage to get this old ship from Vestmannaeyjar to Vík, where it is Information Center in Halldórskaffi.

Goods transported for the first time in 1918

At a district council meeting in 1916 a decision was taken to finance the purchase of a vessel to transport goods from Reykjavik to Vík, the Skaftá river estuary, Hvalsíki and Ingólfshöfði. The idea received widespread support, even teenagers contributed their savings towards the buying of the ship. In 1917 it was agreed to establish a limited company and that the ship should have the name Skaftfellingur. In the spring of 1918, the boat began its first sailing

The first car arrives on board Skaftfellingur

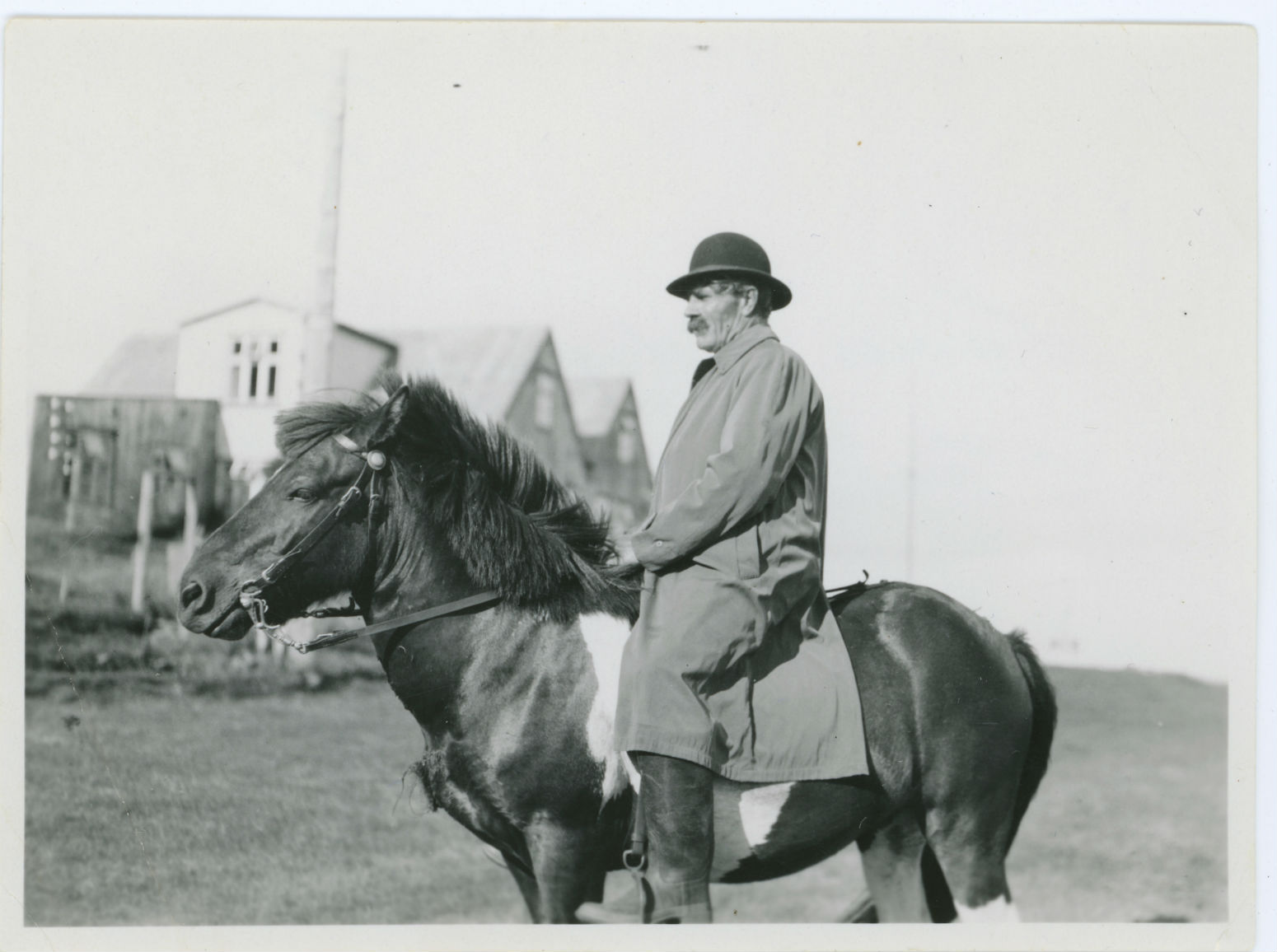

When unloading at the Skaftá river estuary, boats had to be used to ferry the goods from the ship and on to the beach. It required skill to row the boats to shore due to the large waves and sometimes it was necessary to wait until weather conditions improved. Once on land the goods were transported on pack horses. It was difficult to have horses on the sands since there was no grass for grazing, so hay had to be provided for the animals. Locals were employed to see to the unloading and transport. The job was reasonably well paid but hard physical labour. The use of the first cars in 1926 meant the work became easier. However, sometimes it was not always possible to drive a car on the sands and there was nothing for it but to go back to using pack horses.

Katla erupts in the autumn and Skaftfellingur transports meat in the spring

In the autumn of 1918 the subglacial volcano Katla erupted. Cut off, farmers east of the Mýrdal sands could not bring their sheep to Vík for slaughtering. Instead, they were provided with barrels and salt to preserve the meat and rye meal for the making of traditional blood sausage or slátur. In the spring the salted meat was transported on ice down to the Skaftá river estuary and put on board the ship Skaftfellingur. The meat fetched a good price. Being able to transport the meat by ship was fortuitous since it is highly unlikely that the barrels could have been transported to market over land.

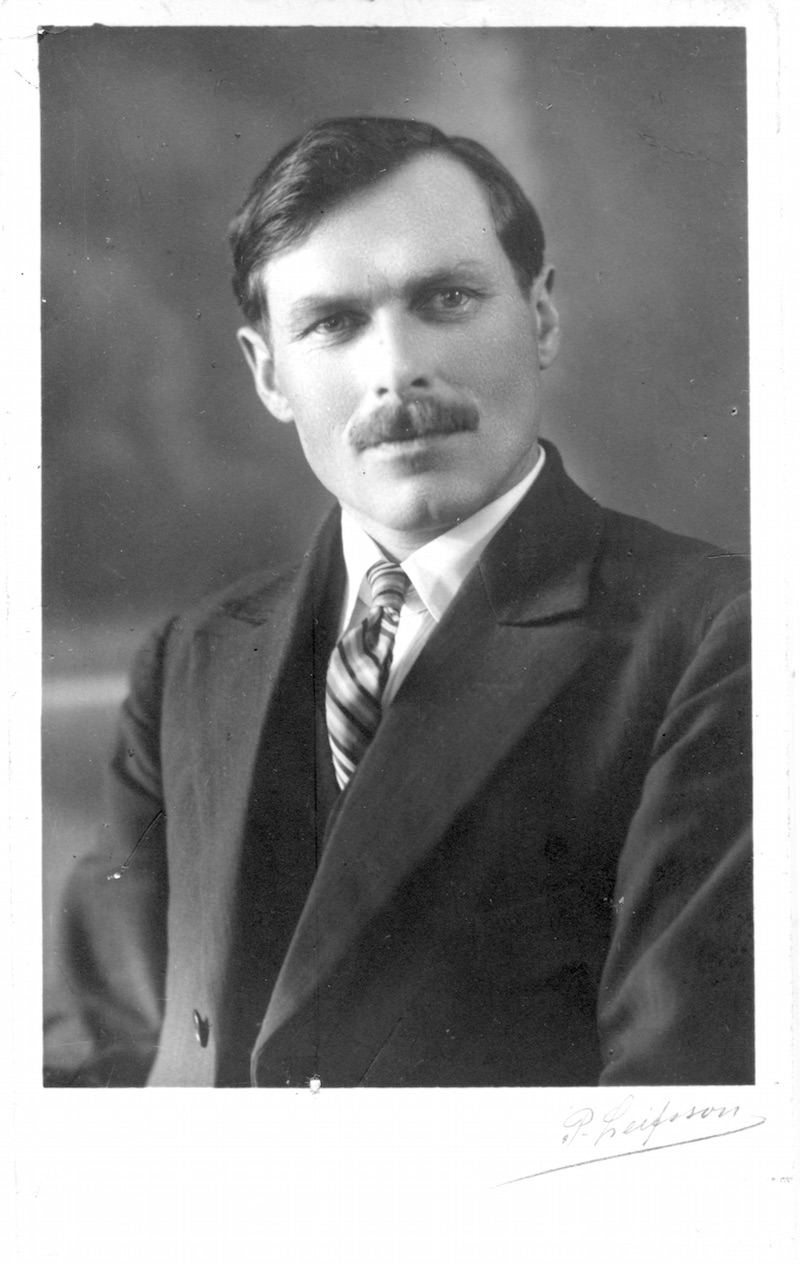

1. Lárus Helgason was Chairman of the Board from the beginning to the end. (Owner. EAV) 2. The Warehouse was big building at that time. (Owner EAV) 3. There were a ferrie near Syðri-Fljótar. (Owner. EAV) 4. Skaftfellingur in his first trip to Vík í Mýrdal 1918.

A warehouse is opened by the Skaftá river estuary

The building of a warehouse by the Skaftá river estuary would be a major commercial improvement for the area. The building had three floors and a floor area of 85 sq. meters. When built it was the largest building owned by the co-op. What made it unique was that it was located so far from any village or town. Today the search and rescue service station near the lighthouse is built on the foundations of this warehouse. In 2009 a group of local volunteers carried out repairs to the old building and put up information signs on its history and commercial activity by the river estuary in bygone times. A telephone line was laid to the warehouse in 1930, which made it easier to communicate with those unloading goods and the ship´s captain as to when best to attempt to bring the provisions ashore.

Skaftfellingur sailed for two decades

Sailings by Skaftfellingur continued without incident for two decades. When it was realized that goods could be successfully unloaded from a ship, larger cargo ships were used. In 1942 the last shareholders´ meeting was held and the decision was taken to wind up the company. By this time the government had agreed to have another cargo vessel supply the southern coast. In addition, transport by land was becoming easier with the construction of more roads and bridges and the growing popularity of the motor vehicle. After the vessel had been sold the company was formally liquidated. There were few assets to be realized, but then the whole function of the company had been not to make a profit, rather to improve communication and living conditions in the area.

1. Bjarni í Hólmi got the first car with Skaftfellingur. (Owner LS) 2. Celebration in Vík í Mýrdal when there were 100 years since the Skaftfellingur came with the first goods to Vík.

Skaftfellingur saved and brought to Vík

But the story of Skaftfellingur is not fully told. When the ship first began sailing there was a young girl in Vík who fell in love with it. She saw its spring arrival in Vík as the harbinger of summer and she had fond memories of all the delightful and beautiful things it brought to her remote village. When she went to the Westman Islands as a young woman in 1973, she spotted Skaftfellingur moored and in a sorry state of disrepair. The young woman´s name was Sigrún Jónsdóttir, an artist well known for her weaving of chasubles. She was determined to bring the old ship back to Vík. But first, she would have to pay off the various creditors who had a claim on the vessel. The owners, of course, were more than happy to get rid of the ship. It was no easy task finding the necessary money, it would take many years and cost Sigrún dearly.